Table Of Content

Now if the intervention is effective we should see that the depression levels have decreased in the student group but that they have increased in the patient group (because they are no longer exercising). If participants in this kind of design are randomly assigned to conditions, it becomes a true between-groups experiment rather than a quasi-experiment. In fact, it is the kind of experiment that Eysenck called for—and that has now been conducted many times—to demonstrate the effectiveness of psychotherapy. Another way to improve upon the posttest only nonequivalent groups design is to add a pretest. In the pretest-posttest nonequivalent groups design there is a treatment group that is given a pretest, receives a treatment, and then is given a posttest.

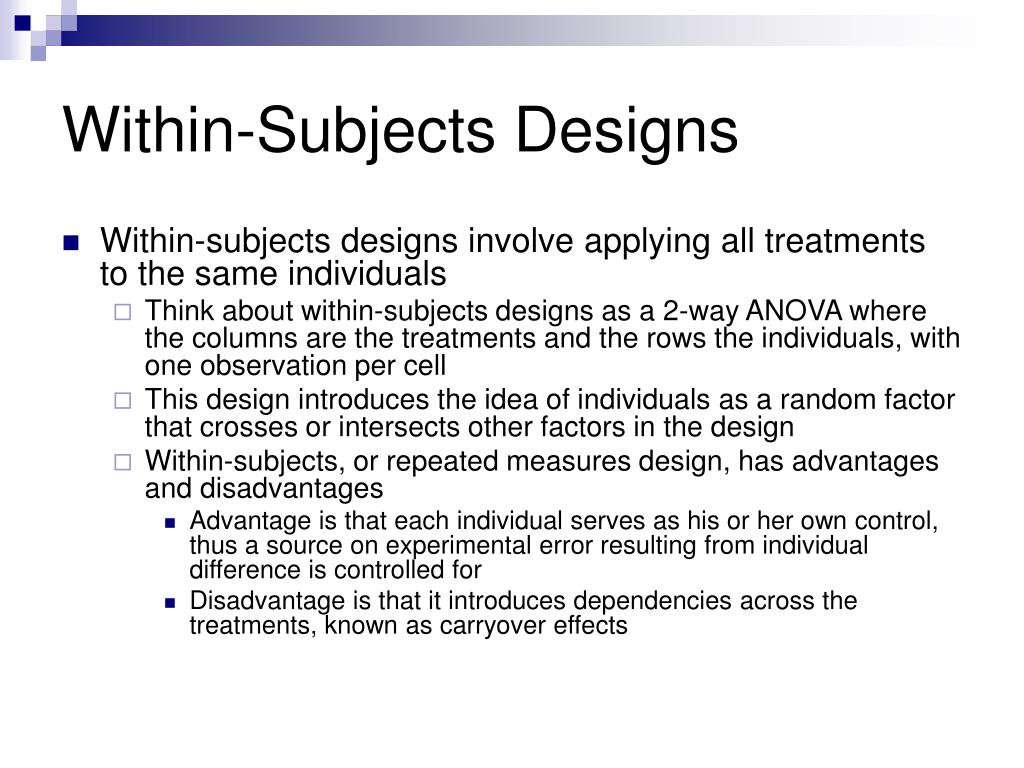

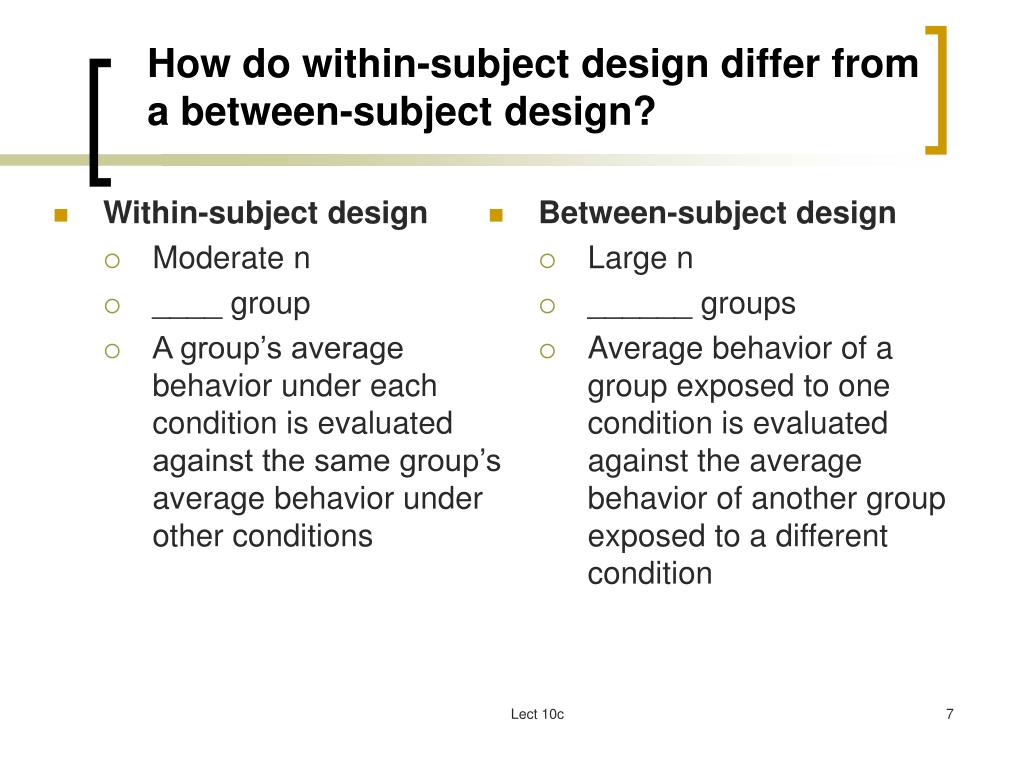

What’s the difference between a within-subjects versus a between-subjects design?

National parochialism is ubiquitous across 42 nations around the world - Nature.com

National parochialism is ubiquitous across 42 nations around the world.

Posted: Thu, 22 Jul 2021 07:00:00 GMT [source]

In a no-treatment control condition, participants receive no treatment whatsoever. A placebo is a simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that should make it effective, and a placebo effect is a positive effect of such a treatment. Many folk remedies that seem to work—such as eating chicken soup for a cold or placing soap under the bedsheets to stop nighttime leg cramps—are probably nothing more than placebos. Although placebo effects are not well understood, they are probably driven primarily by people’s expectations that they will improve. Having the expectation to improve can result in reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, which can alter perceptions and even improve immune system functioning (Price, Finniss, & Benedetti, 2008). One is that it controls the order of conditions so that it is no longer a confounding variable.

Within-Subject Designs Require Fewer Participants

The right column depicts contrasts comparing sensitivity (dL’) and response bias (CL; both on the logit scale, see in-text for details) as a function of production (silent, aloud); thick lines represent the 50% HDI and thin lines represent the 95% HDI. The proportion of know responses is estimated only for those trials not receiving a remember response (e.g., Yonelinas & Jacoby, 1995). The left column depicts the back-transformed estimated proportion of old, remember, and know responses for Experiment 1a as a function item type (foil, silent, aloud). In the example given, we would get evidence for the efficacy of the treatment in two different samples (patients and students). Another strength of this design is that it provides more control over history effects.

Types

This means that researchers must choose between the two approaches based on their relative merits for the particular situation. Bruce Moseley and his colleagues conducted a study on the effectiveness of two arthroscopic surgery procedures for osteoarthritis of the knee (Moseley et al., 2002). The control participants in this study were prepped for surgery, received a tranquilizer, and even received three small incisions in their knees. The surprising result was that all participants improved in terms of both knee pain and function, and the sham surgery group improved just as much as the treatment groups. This possibility means that researchers must choose between the two approaches based on their relative merits for the particular situation. Individual participants bring in to the test their own history, background knowledge, and context.

If these conditions (the two leftmost bars in Figure 6.2 “Hypothetical Results From a Study Including Treatment, No-Treatment, and Placebo Conditions”) were the only conditions in this experiment, however, one could not conclude that the treatment worked. It could be instead that participants in the treatment group improved more because they expected to improve, while those in the no-treatment control condition did not. Researcher Michael Birnbaum has argued that the lack of context provided by between-subjects designs is often a bigger problem than the context effects created by within-subjects designs. To demonstrate this problem, he asked participants to rate two numbers on how large they were on a scale of 1-to-10 where 1 was “very very small” and 10 was “very very large”. One group of participants were asked to rate the number 9 and another group was asked to rate the number 221 (Birnbaum, 1999)[1].

Method

One is that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to each condition (e.g., a 50% chance of being assigned to each of two conditions). The second is that each participant is assigned to a condition independently of other participants. Thus one way to assign participants to two conditions would be to flip a coin for each one. If the coin lands heads, the participant is assigned to Condition A, and if it lands tails, the participant is assigned to Condition B. For three conditions, one could use a computer to generate a random integer from 1 to 3 for each participant. When the procedure is computerized, the computer program often handles the random assignment.

Consider an experiment on the effect of a defendant’s physical attractiveness on judgments of his guilt. Again, in a between-subjects experiment, one group of participants would be shown an attractive defendant and asked to judge his guilt, and another group of participants would be shown an unattractive defendant and asked to judge his guilt. In a within-subjects experiment, however, the same group of participants would judge the guilt of both an attractive and an unattractive defendant. One is that random assignment works much better than one might expect, especially for large samples.

These factors could very easily become confounding variables and weaken the results, so researchers have to be extremely careful to eliminate as many of these as possible during the research design. These disadvantages are certainly not fatal, but ensure that any researcher planning to use a between subjects design must be very thorough in their experimental design. The main disadvantage with between subjects designs is that they can be complex and often require a large number of participants to generate any useful and analyzable data. Because each participant is only measured once, researchers need to add a new group for every treatment and manipulation. A between subjects design is a way of avoiding the carryover effects that can plague within subjects designs, and they are one of the most common experiment types in some scientific disciplines, especially psychology.

Let’s Drive Results Together!

As an initial analysis, the remember and know responses were collapsed into old responses (representing having made either response), so that hits and false alarms could be calculated. We then applied a multilevel logistic regression model with item type (foil, silent, aloud) as a fixed effect. Because item type was a categorical variable, the silent and aloud conditions were each dummy coded as 0 or 1 with foil serving as the relevant intercept. The first nonequivalent groups design we will consider is the posttest only nonequivalent groups design.

The between-subjects design is conceptually simpler, avoids order/carryover effects, and minimizes the time and effort of each participant. The within-subjects design is more efficient for the researcher and controls extraneous participant variables. Our goal was thus to investigate whether the production effect differentially relies on recollection and familiarity in within-subject and between-subjects designs. Experiments 1a and 1b compared the magnitude of the production effect, as indexed by estimates of recollection and familiarity across between- and within-subject designs using remember-know responses (Gardiner, 1988; Tulving, 1985). Experiments 2a and 2b next replicated our results using estimates of recollection and familiarity derived from simple confidence ratings using a dual-process signal detection framework (Yonelinas, 1994, 1997).

Carryover effects between conditions can threaten the internal validity of a study. A carryover effect is an effect of being tested in one condition on participants” behavior in later conditions. Shows how each level of one independent variable is combined with each level of the others to produce all possible combinations in a factorial design. Regardless of whether the design is between subjects, within subjects, or mixed, the actual assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions is typically done randomly. In that case, the use of within subject design will be impossible because the repeated use of the same actions will badly affect the study`s objectivity.

Participants in all conditions have the same mean IQ, same socioeconomic status, same number of siblings, and so on—because they are the very same people. Within-subjects experiments also make it possible to use statistical procedures that remove the effect of these extraneous participant variables on the dependent variable and therefore make the data less “noisy” and the effect of the independent variable easier to detect. However, not all experiments can use a within-subjects design nor would it be desirable to do so. An alternative to simple random assignment of participants to conditions is the use of a matched-groups design. Using this design, participants in the various conditions are matched on the dependent variable or on some extraneous variable(s) prior the manipulation of the independent variable.

For example, a researcher with a sample of 100 college students might assign half of them to write about a traumatic event and the other half write about a neutral event. It is essential in a between-subjects experiment that the researcher assign participants to conditions so that the different groups are, on average, highly similar to each other. This is a matter of controlling these extraneous participant variables across conditions so that they do not become confounding variables. A good rule of thumb, then, is that if it is possible to conduct a within-subjects experiment (with proper counterbalancing) in the time that is available per participant—and you have no serious concerns about carryover effects—this design is probably the best option. This difficulty is true for many designs that involve a treatment meant to produce long-term change in participants’ behavior (e.g., studies testing the effectiveness of psychotherapy). The primary advantage of this approach is that it provides maximum control of extraneous participant variables.

In research on the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments, this type of experiment is often called a randomized clinical trial. The primary way that researchers accomplish this kind of control of extraneous variables across conditions is called random assignment, which means using a random process to decide which participants are tested in which conditions. Random sampling is a method for selecting a sample from a population, and it is rarely used in psychological research. Random assignment is a method for assigning participants in a sample to the different conditions, and it is an important element of all experimental research in psychology and other fields too. The primary way that researchers accomplish this kind of control of extraneous variables across conditions is called random assignment, which means using a random process to decide which participants are tested in which conditions.

At test, words appeared individually in a black font, and participants had to identify whether the word was studied (i.e., old) or new. Participants made their choice by clicking a value on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (sure new) to 6 (sure old), shown directly below each word at test. Participants were encouraged to use the entire scale over the course of the test, and to avoid strategies that would result in binary response data, such as selecting 6 and 1 or 5 and 2 for all their responses. In the standard spacing condition, the 120 studied words were randomly intermixed with 120 new words. In the short and filler conditions, the 60 studied words were randomly intermixed with 60 new words, randomly drawn from the full word pool.

No comments:

Post a Comment